Garry Edwards

Moderator

- Messages

- 12,333

- Name

- Garry Edwards

- Edit My Images

- No

Do you groan when you hear 'physics'...?

I was having a conversation today with someone who simply didn't realise that the reason I'm able to work so quickly in the studio and hardly ever need to adjust my lighting (much) is because my whole approach is physics-based.

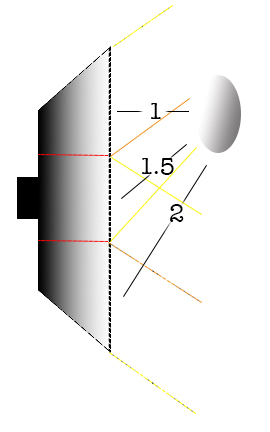

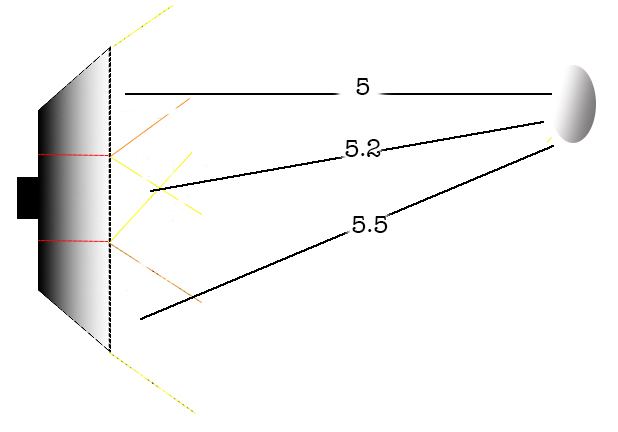

to be more specific, it's all about the practical application of Newton's Inverse Square Law, which affects not just how much light reaches the subject but also how much light reaches the various parts of the subject, how it affects the background, how it affects the softness or otherwise of the lighting and so on.

And the fact that when we understand the technical aspects (of anything) to the point where we don't need to think about them, we have the capacity to be creative, because no energy is being expended on technical aspects - just as an experienced driver can watch the road without thinking about changing gear.

So, the question is this.

If I can make a good job of explaining simple principles in a simple way in a video, will people watch it and learn from it?

Or will the subject matter kill the view numbers?

Edit: I'm better at physics than typing: The title sould say simple, not simply

I was having a conversation today with someone who simply didn't realise that the reason I'm able to work so quickly in the studio and hardly ever need to adjust my lighting (much) is because my whole approach is physics-based.

to be more specific, it's all about the practical application of Newton's Inverse Square Law, which affects not just how much light reaches the subject but also how much light reaches the various parts of the subject, how it affects the background, how it affects the softness or otherwise of the lighting and so on.

And the fact that when we understand the technical aspects (of anything) to the point where we don't need to think about them, we have the capacity to be creative, because no energy is being expended on technical aspects - just as an experienced driver can watch the road without thinking about changing gear.

So, the question is this.

If I can make a good job of explaining simple principles in a simple way in a video, will people watch it and learn from it?

Or will the subject matter kill the view numbers?

Edit: I'm better at physics than typing: The title sould say simple, not simply

Last edited:

] but like I say, teach me an alternative way of working in a way I can understand and I will be there.

] but like I say, teach me an alternative way of working in a way I can understand and I will be there.